John Dewey's Unrecognized Triumph

|

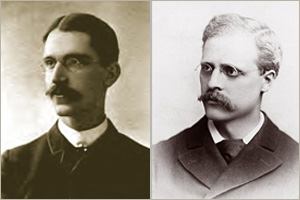

| John Dewey

(L) and Calvin Brainerd Cady at Michigan in the

1880s. Dewey photo from the John Dewey

photograph series, the Bentley Historical Library,

University of Michigan.; Cady photo from the

U-M News and Information Faculty/Staff portraits,

the Bentley Historical Library, University

of Michigan.. |

| |

Recent research has proven that Cornish

was in the forefront of the Progressive movement in

adult education, tracing its roots to the thought

of John Dewey. This means that Cornish has a deep

pedigree in American education, and that Dewey

had a great success in an arena he might not have

imagined.

Anyone involved in education knows

who John Dewey is: he’s the person most responsible

for the rise of progressivism in education. Starting

with his work with school teachers at the University

of Michigan and accelerating with his famed Laboratory

School at the University of Chicago at the end of

the 19th century, Dewey set the standard for the movement

that rejected the old-style, regimented educational

system. After the turn of the century, this time from

his chair of philosophy at Columbia, he was instrumental

in bringing his way of teaching and learning to adult

education at a small but elite group of colleges,

especially The New School in New York and Bennington

College in Vermont.

We now know that Dewey’s influence was also a key constituent of the pedagogy

at the Cornish School. Cornish was arguably the first institution to use his

philosophy for adult education in America. At its founding in 1914, Cornish

offered elementary education. But that quickly began to change and older students

were enrolled. Adult education was firmly established at Cornish

with the founding of its Theater Department in 1918, and the first Dewey-led

adult educational facility, the New School, was founded a year after, in 1919.

The relationship of Dewey to Cornish College of the Arts has gone almost completely

unnoticed both at the college and throughout higher education in this country.

In the first years of the 20th century, Nellie Cornish was casting about for

new methods of teaching music that would be compatible with her own views.

In a sense, she was looking for validation of the liberal ideals she had absorbed

from her father and from her own search for quality. She had gone so far as

to begin research on a book on the teaching of music, when in her studies her

eye fell on name of Calvin Brainerd Cady. 1 She had noted his work before

in a variety of music publications: “And strangely enough, in some ways, his

ideas brought back to me what my Father used to say about the ways and needs

of education.” 2

From her reading, Cornish discovered Cady was to teach a six-week class in Los Angeles in June of 1911. That summer, she boarded a passenger ship for California. On the first day, Cady opened with a lecture entitled “Education of the Individual Through the Realm of Music and Allied Arts.” Much of his philosophy of education can be seen in miniature in this title: first, an emphasis on the individual student; second, that education by means of music was indeed “education” not the acquisition of a set of skills or an extracurricular activity; and third, that the arts are or should be allied in the educational process. “Mr. Cady’s words remained a guiding light in all my future work,’ Cornish wrote, “and I used them as a touchstone.” 3 In 1916, two years after Cornish founded her school, Calvin Cady joined as Dean of Education. 4

Calvin Brainerd Cady was born in 1851 in the tiny town of Barry in Illinois.

He was from an old Yankee family, the son of a minister. He studied at Oberlin

College in the college preparatory program and conservatory, graduating from

the Oberlin Conservatory in 1872. From there he traveled to Leipzig, in Germany,

and studied piano and organ in what was at the time a world musical center.

Cady is referred to as “Dr. Cady” in some quarters, so may have had that degree

from Leipzig. As a conservatory within a college, Oberlin may have given Cady

a wider view of education and music, but Leipzig was conservatory training.

The two experiences no doubt gave him an expansive view of the problems of

music education. Oberlin may have been able to display for Cady musical training

in the context of a rounded education.

In 1880, Cady came to the University of Michigan because the regents of the university wanted to add music to the curriculum. He was hired with the title of “instructor” and given the task of setting up a department. This was not a straightforward task: only courses about music were considered proper fare for a university curriculum, not the making of music itself. Cady was to teach the history of music, the science of music, music theory—and so forth—at the university. The workaround with regard to instrument and voice instruction was for Cady to start an independent school of music, with the blessings of the university, to run parallel to his teaching at Michigan. This was the Ann Arbor School of Music. Today’s Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance dates its founding to 1880, the year Cady arrived to teach in Ann Arbor and started up the school of music there.

This ungainly setup of the two independent but parallel curricula lasted for five years, when changes in the charter allowed the university to bring Cady’s Ann Arbor School of Music together with its undergraduate courses in music. In 1885, Calvin Cady was promoted from instructor to professor of music at Michigan. The indications are that the instrument and voice instruction at the Ann Arbor School of Music were made part of the curriculum at the university. Cady is thus credited with establishing “one of the first bachelor’s and master’s degree programs in music in the United States.” 5

The year 1885 is notable for another reason. In that year, a young John Dewey arrived in Ann Arbor to teach philosophy, fresh from receiving a doctorate from Johns Hopkins.

There is much we don’t know about Calvin Cady during his time at Michigan, the

most tantalizing and most frustrating mystery being his relationship with John

Dewey. That he had one there can be no doubt, as the faculty numbered not a

hundred. Also, Cady’s name crops up in Dewey’s extant correspondence, though

admittedly these are passing references. 6 Yet it seems probable

the two men were close at Michigan when the work they would undertake together

some years later in Chicago is taken into consideration.

Dewey was not fixed on educational theory when he arrived in Ann Arbor. His

dissertation at Johns Hopkins did not concern education, it was on Kant's

“psychology of spirit.” 7 Michigan was a pioneer in putting aside

entrance examinations in favor of accepting diplomas from secondary schools.

[pamphlet] This involved faculty members assessing the state of the schools

wishing to have their students admitted, and among them was John Dewey. A mere

year after arriving at the university, in May of 1886, Dewey was so involved

that he was instrumental in founding The Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club, bringing

together Michigan faculty members with secondary school teachers in the state.

The club “provided Dewey with an important new forum for discussing his developing

concepts of education.” 8 Dewey scholar Brian Williams notes: “Dewey

expressed the importance of his time at Michigan to the formation of his educational

philosophy, writing, ‘[I]t was in Ann Arbor that I began my teaching activities.

It was there that my serious interest in education was aroused.’” 9

Cady’s name appears nowhere on the rolls of the Michigan

Schoolmasters’ Club. Cady’s entry into educational

theory isn’t documented in any other way, but surely

splitting his time between teaching music as an

intellectual subject in a university curriculum

and teaching actual music-making elsewhere must

have presented enormous questions about the nature

of how we learn music and what its overall educational

value might be. His interest would become a book

in the decade following.

So it was during their time in Ann

Arbor that both men became interested in educational

theory; again, we know this because of what they would

go on to do in Chicago. But did they develop ideas

together, formally? It is unclear, but it has to be

considered likely. Both men came to Ann Arbor to teach

their separate subjects, and both departed the university

with an active interest in educational theory. Something

can be made of that.

Cady left Michigan in 1888. According to a history of the university, he was disappointed in the level of commitment shown by his students to performing. It is also possible that the university wanted to alter the position of music; certainly this is what came to pass. After Cady resigned his professorship, Albert A. Stanley came in as head of the music department. Within a few years, according the UM historian Wilfred Shaw writing in the 1920s, the university established a school of music that was “closely associated with the work of the University though not in any way a part of it.” The history taken as a whole, it is as though the university was trying the idea of a music department on for size, with Cady hired to oversee the experiment. In any event, the university clearly decided that music did not belong as part of a university’s curriculum, and that they would go another direction. The department was abolished in favor of a separate school of music based on Cady’s Ann Arbor School of Music.

John Dewey also left Michigan in 1888. He had been offered a faculty position

at the University of Minnesota. One has to consider that the two leaving the

same year might be connected, but tempting as it might be to go in that direction,

it is most certainly just a coincidence. Dewey was just starting a family,

and Minnesota offered more money. There was certainly no bad blood between

Dewey and Michigan; he moved back to Ann Arbor a year later to assume the chair

of the university’s philosophy department.

After leaving the University of Michigan, Cady took a position in 1888 at the Chicago Conservatory of Music, which afforded him a lovely home on the lakefront north of the city in Evanston. Sometime after accepting the position, Cady’s interest in educational theory led him to begin “normal classes”—teacher training—in elementary music education.

In 1892, Cady left Chicago for Boston. There, he was listed as a music teacher at 900 Beacon Street. What prompted his decision to move to that city isn’t known, but by the time he was working with Nellie Cornish, he was an adherent of Christian Science, and Boston was the home of what was then a new religion. The church had only been established by Mary Baker Eddy a dozen years before, in 1879 and moved to Boston in 1882. Cady’s home on Beacon Street was only three-quarters of a mile across the Fenway from the Christian Science Mother Church in Boston’s Back Bay area, whether by chance or by design. Given how new the religion was in the early ’90s and not widespread, it stands to reason that Cady became an adherent during his time in the city. Religion was front-and-center in his thinking on education in music, and his conversion to Christian Science, which emphasises a mix of practicality and spirituality, was well suited to his needs.

In 1894, Calvin Cady left Boston and returned to Chicago. That same year, John Dewey also arrived in there. Dewey had been offered a professorship and the chair of the philosophy department at a newly formed research university, the energetic University of Chicago. It is not known whether Cady and Dewey’s move to the city was made jointly, or whether it is yet another happy chance.

Dewey soon expanded his role at Chicago by also becoming the chairman of the teacher training program, an indication of how important education theory had become to him. Soon thereafter, in 1896, he founded what is regarded as the seminal progressive experiment in education, the University Elementary School, which was later to be renamed the University of Chicago Laboratory School.

Cady was on the scene at the new school, possibly from the start: “The method

of teaching music was that of Professor Calvin B. Cady, a musician with the

point of view of an educator.” 10 The day-to-day teaching of music at the Laboratory

School was undertaken by Cady’s students, and there is no evidence that Cady

himself was involved. The source of these students was almost certainly his

own music teachers’ training program, which he seems to have been running since

his return to Chicago. By 1897 and ’98, advertisements for these classes appeared

in music periodicals. At any rate, students of his were on hand to begin teaching

music at the Laboratory School by the time of its opening in 1896. HIs music

education classes were held at Chicago’s Fine Arts Building at 410 South Michigan

Avenue, the same structure that would become home to the Chicago Little Theatre

in 1912—which would have an important connection to The Cornish School. Cady’s

offices down the street in Chicago’s Auditorium Building. 11

The reunion of Dewey and Cady at the Laboratory School was significant in that

both men were concerned not only with educational theory, but with teaching

teachers—"normal education." Normal education is, of course, the natural outgrowth

of educational theory, since it is a cadre of teachers which can move theory

into practice. There is a greater significance still: the

Laboratory School wasn’t an existing school whose practices were being improved

upon, it owed its very existence to educational theory. Both men would be a

part of founding schools which were the embodiment of theory, Dewey with The

New School of Social Research and Bennington College and Cady with his own

elementary school of music in Portland and ultimately with The Cornish School.

How long Cady was connected to the Laboratory School in Chicago is not clear,

but by 1901, Cady was again to be found living in Boston. 12 There had been

changes at the Laboratory School that may have prompted this move. “In 1901

the University of Chicago combined the Laboratory School with the Chicago Institute,

a private progressive normal school that had been founded by Francis W. Parker.”

13 This change was not made with John Dewey’s cooperation, and led in due course

to his leaving the University of Chicago for Columbia University in New York

City in 1904.

In 1902, Cady published a book on teaching music to children, Music-Education:

An Outline on Boston’s Stanhope Press. There are many points of comparison

between Dewey’s thoughts and those presented in the book. Cady drives home the

idea that the teacher must build on the child’s interests. Also reflecting Dewey

is that Cady stresses that what he is presenting is not a system, but as an example.

14

At Columbia University, Dewey held professorships in philosophy at the university and its Columbia Teachers College concurrently, a setup not too unlike the one he had left in Chicago, with the exception that he was not the department chair—yet. Three years later, in 1907, Cady is also recorded as living in New York City lecturing in pedagogy at the Teachers College and additionally, a year later, at the Institute for Musical Arts, the school subsumed by the Juilliard Foundation.

It is a pattern that cannot be ignored even as its meaning is unclear: Cady and Dewey were living and working in the same locale once again, this time in New York. Whether Cady’s appointment at the teachers college had anything to do with Dewey’s influence is yet another tantalizing, aggravating, unknown. Ann Arbor, Chicago, New York: the two men were thrice to be found in the same city, and more than that, at the same institutions. It simply can’t be coincidental. Yet we have almost no direct contemporary evidence of their working together as thinkers on education, other than that Dewey selected Cady to design the music program at the Laboratory School, and we don’t know his reasons for that. There is no correspondence from Dewey on any work undertaken with Cady, and none of Cady’s papers have been unearthed—if they exist at all—that could set the mind to rest.

Yet there is indirect evidence. Cady split time in the 1910s and ’20s between

his elementary school in Portland and the Cornish School in Seattle. There

can be little doubt that his philosophy was the same for both institutions.

In 1949, Gobindram J. Watumull, an Indian-American philanthropist, referred

to Cady’s Portland school when he wrote Dewey congratulating him on his 90th

birthday. “I don't suppose when you first began to think your great thoughts

on democracy and education, how far-reaching the effects would be,” wrote Watumull.

“They have had a very intimate effect in our own family beginning with my younger

brother's education in the Music-Education School in Portland, Oregon, founded

by your late good friend Calvin Brainerd Cady, and based on your ideals.” 15

Watumull’s relation of John Dewey’s thought to Calvin Cady is bolstered by an

official Cornish School history written in 1959. It shows that Cady's Dewey-based

practices at his own school were similar to those at Cornish. It also unequivocally

ties Dewey to the underlying philosophies of the Cornish School. The description

deepens Cady's connection to Dewey, calling him a disciple.

The year 1959 may seem long after

the events of the early 1900s, but there were some

on staff who would be well able to inform the writer

of this history. Two women who had been with Nellie

Cornish from the beginning, Martha Sackett and Ellen

Wood Murphy were still around to be consulted. They

studied with Cady at the School, and Sackett also

studied with him in Los Angeles, as Nellie had. They

worked closely with him all the way till his death

in 1928. Sackett and Murphy would have been well acquainted

with Cady’s thinking on all matters, possibly better

than anyone else.

There is one last puzzle to tantalize us in the Cady/Dewey story, acting as a

sort of coda. In 1918, John Dewey traveled west on vacation from early May

to the end of June, ending up in Lake Louise in Canada. He stopped in Portland

on June 24, staying for a day, or perhaps two. He left no information on what

he did there. 17 It was not really enough time to do much sightseeing, but

it is enough time to call on an old friend. Cady was then in Portland with

his school, and presumably available for a visit—in fact, his flat was a short

walk from the train station. Was Cady the reason Dewey paused in Portland?

Stepping back from this narrative and into my own experience with the subject

of the Cornish School, it was clear to me that—though I saw no connection at

the time—Nellie and Cady’s ideas were clearly harmonious with Progressive

values. Early on, I saw this simply as being of its time and in the nature

of teaching art. Now, of course, it is clear that the harmony was no coincidence.

— MMB

- Cornish, Nellie C. Miss Aunt Nellie: The Autobiography of Nellie C. Cornish.

Ellen Van Volkenburg and Edward Nordhoff Beck, eds. Seattle,

University of Washington

Press, 1964; p 72.

- Miss Aunt Nellie; p 54.

- Miss Aunt Nellie; pp 72-5.

- Miss Aunt Nellie; p 99.

- Shiraishi

Fumiko. Calvin Brainerd Cady: Thought and Feeling in the Study of Music. JRME

Volume 47, Number 2, pp 151

- The Correspondence of John Dewey. Letter 00056, John Dewey to Alice

Chipman Dewey, April 4, 1887. Letter 00189, John Dewey to Alice Chipman, Frederick

A., and Evelyn Dewey,

September 14, 1894.

-

John

Dewey at Johns Hopkins (1882-1884) George Dykhuizen Journal of the History

of Ideas, Vol. 22, No. 1. (Jan. - Mar., 1961), pp. 103-116.

- Williams,

Brian A. Thought and Action: John Dewey at the University of Michigan , Bulletin

No. 44, July 1998; Ann Arbor, Bentley Historical Library, The University

of Michigan, p 20.

- Williams, p 1.

-

Mayhew,

Katherine Camp, and Anna Camp Edwards; The Dewey School: The Laboratory

School of the University of Chicago 1896-1903. Introduction by John Dewey.

New York & London: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1936. p. 355.

- Etude magazine, advertisement.

- x

- x

- Cady, Calvin Brainerd, Music-Education: An Outline, vol 1. Boston,

Stanhope Press, 1902. Page xi.

- Gobindram J. & Ellen Jensen Watumull, correspondence with John Dewey,

letter 11742. The Correspondence of John Dewey, 1871-1952, Hickman,

Larry ed. Past Masters (InteLex Corporation), online. October 10, 1949.

- x