Bonnie Bird & Company

There is hidden drama behind a series of familiar photographs from Cornish’s “golden years.” Unpopular, unappreciated, seemingly dead-end: no one caught up in the events of 1937-40 could have predicted how huge the work of an ad-hoc dance-theater company set up by Director of Dance Bonnie Bird would be.

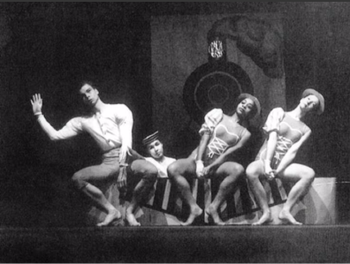

|

| Merce Cunningham, Bonnie Bird,

Syvilla Fort, and Dorothy Herrmann in 3 Inventories

of Casey Jones, choreographed by Bonnie Bird, set

by Xenia Cage, music by Ray Green under the direction

of John Cage, the Cornish School, 1938. Photo by

Phyllis Dearborn © Michael Cunningham; from the

Bonnie Bird Collection at Trinity Laban Conservatoire

of Music and Dance. |

More than

a half century ago, Seattle photographer Phyllis

Dearborn froze on black-and-white film a moment from a whimsical bit of choreography.

There are four dancers in the shot, but our attention falls first on the familiar

face of the young man with the curly hair. Almost anyone connected with the

college can tell you who it is: Merce Cunningham. As everyone knows, Cunningham

went on from Cornish to become one of the major figures of 20thcentury dance,

and any pictures of him that show him at work are treasured keepsakes at Cornish,

icons of the school’s glory days. The images are iconic, too, for one who is

not pictured but happily haunts the photos—the musical director of the piece,

John Cage. Almost as many know that he, too, went on to become a major figure

in 20th century art, as a composer. Cornish introduced Cunningham and Cage,

and they entered into a life-long professional and personal partnership. Called

3 Inventories of Casey Jones, the piece was a fun romp—but the fun so brilliantly

captured in the photo masked a very serious drama that was unfolding at Cornish.

There is, in fact, something almost Shakespearean in the size of it. The story

behind the photo puts in stark contrast the brilliant impulses that made Cornish

an internationally important center of arts education in the 23 years it had

existed and those darker ones that pulled it back towards obscurity. One might

say it is the story of greatness laid low by what the Greeks called hamartia—a

heroic flaw.

The year was 1937

This is significant in setting the drama because it is a mere two years before Nellie Cornish would leave the school that bore her name, a departure that ended an era, a philosophy, and a revolution in arts education and began a period of tumult and bad feeling. At the center of the drama was the young head of the Dance Department, a product of the Cornish School and a favorite of Nelly Cornish. This dancer, choreographer, and educator would go on to great success, alumna Bonnie Bird '27-30.

Bonnie Bird

Bird was, like Nellie Cornish, a daughter of the Northwest: straightforward, tough-minded, resilient, and hard-working. Born in Portland the year Nellie founded Cornish, 1914, Bird grew up both in Seattle and in the countryside beyond its city limits. A great lover of horses, her highest aspiration as a girl was to become a rodeo trick rider and roper, according to her biographer, Karen Bell-Kanner. This plan for her development was undermined the day in Seattle when she saw her next-door neighbor, the son of her mother’s friend, doing his ballet exercises. The young dancer’s name was Caird Leslie. He had been dancing with Adolph Bolm, a partner to Anna Pavlova in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Some time later, Leslie took her backstage to meet Pavlova when the great dancer came to Seattle on tour. Young Bonnie migrated in her dreams from “Bonnie Bird, rodeo queen” and “Bonnie Bird, veterinarian” to “Bonnie Bird, prima ballerina.”

At about the age of nine, in about 1923, Bonnie became one of Leslie’s first ballet students in his new school. Worth noting is that it is likely that Karen Irvin, longtime head of Dance at Cornish from 1954 to 1979, took classes with her: Irvin listed Leslie as her teacher and she and Bonnie Bird were roughly the same age. Irvin would go on to form the influential Cornish Ballet that was the center of the art in the Northwest for a generation.

In 1927, when Bird was 13, Leslie folded his ballet school into the Cornish School and became head of Dance. It was the second go-round for Leslie at the Cornish School, and, as it turned out, his latest stay was no more successful than it had been before. By 1928 he was gone and the future of ballet instruction was in question. Nellie called each dance student into her office to deliver the news personally that ballet was being deemphasized in favor of modern dance [see the May 2015 Cornish magazine feature on Louise Soelberg, page 10]. “Modern” was, at the time, still very much developing as a form of dance. Bell-Kanner describes the Nellie’s rationale for the decision, as told to Bird: “Miss Cornish told her she was convinced that the best way to educate young dancers was to stimulate them to make their own artistic decisions, and ballet training did not prepare them for this.”

Ever strong-willed and rebellious, Bird organized an underground ballet class at Cornish in protest. This revolt was shrugged off by Nellie Cornish, it seems, who no doubt saw something of herself in Bird. “She was my mentor,” Bird said of Nellie, “and she bossed me around a lot. She also thought I was one of the most stubborn [sic] that she ever knew.” But the new head of Dance, Louise Soelberg ’26, slowly won her over to modern. At a time when everyone in the world was trying just to define what modern dance was, Soelberg was teaching the newer form by teaching ballet alongside it—the very recipe used at Cornish today. Her progress was such that Bird was ready in 1930 when a dancer and choreographer on the upsweep of a meteoric rise arrived to fill what had become an important role at Cornish, running the summer program. This was Martha Graham.

Martha Graham

“When this fierce, dynamic, and startling woman—very small, very fiery—the impact of her classes was extraordinary,” Bird recounted to Bell-Kanner about meeting Martha Graham. Whatever longing Bird still felt for classical ballet was washed away. Graham was also impressed with Bird: she invited her to New York to prepare for her company—as soon as she finished high school. Bird was able to graduate high school in August of 1931, finishing classes there at the expense of work at Cornish. She left for New York with Nellie’s blessing, but without finishing the dance program at the School—it was not unusual for young artists to leave early for professional opportunities.

Bird arrived in New York to find two other Cornish students already brought in by Graham, Dorothy Bird (no relation) and Nelle Fisher. As part of their training in preparation for dancing in Graham’s company, they took acting classes at the famed Neighborhood Playhouse. Bird began a long and fruitful relationship with Martha Graham, first as student and ward, then as a dancer in her company, the Graham Group. Later, her can-do attitude made her a trusted assistant and led at last to her certification as a teacher of Graham technique.

It was an exciting time for Bird, but after five years of intense work and touring with Graham, she felt ready to strike out on her own. There were just the beginnings of degree programs in America, and she was setting out with what was as complete an education in dance as was available at the time. She found her new opportunity where she had bloomed as a dancer; Nellie Cornish hired her in the spring of 1937 as the new head of her school’s Dance Department.

Cornish and “Bonnie Bird and Group”

Bird was excited at the prospect of returning home to Cornish. She was just 23 years old. Her return to the Northwest had just included a highly successful workshop at the University of Washington, and she had suggested to Nellie Cornish that she could be advertised as the only certified teacher of Graham Technique on the West Coast.

But the circumstances of Bird’s return to Cornish were unsettled at best and nightmarish at worst. The school was in the decline of the Nellie years. In 1937-38, Nellie was waging a running battle with the directors over money and the structure of the school’s curriculum. In these last years, she described herself as “a tired, sick woman” and she admitted to barely knowing several members of the board of the school she had founded. Cornish hired Bird in 1937, but was so distracted she didn’t advertise the classes at all. When Bonnie Bird arrived for the fall term, she was crushed to find this out, and at its result: she would have just a handful of students.

“I expected to start reconstruction from the bottom up,” Bell-Kanner quotes Bird as saying, “but I never realized how barren the bottom could be.”

Faced with the disappointment of the limited enrollment, she could have meekly held her tiny classes and collected her pay and had done with it—but she had the gumption that has so often characterized Cornish alumnae. In modern parlance, Bird decided to look at the diminutive size of the department as “not a flaw, but a feature.” She decided to pour her considerable creative energy into forging a unique learning environment for her students and her school. It resulted in the creation of what was for all intents and purposes a collaborative dance-theater company. By May 6, 1938, when Bird and her dancers took part in a fund-raiser to support the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, they had an identity, appearing as “Bonnie Bird and Group” – elsewhere billed as “Bonnie Bird and her Dance Group.” It is evident that Bird thought of her collection of students and teachers as a production unit.

Syvilla Fort and the Dancers

Luckily, two of Bird’s small contingent of dance students were quite good: Dorothy Herrmann and Syvilla Fort. The two were in almost all the photos of “Bonnie Bird and Group.” Dorothy Herrmann, like Bird before her, was to have the opportunity to leave Cornish early to dance with Martha Graham, but opted instead for married life. Her classmate Syvilla Fort would go on to become an important figure in American dance.

Fort can be seen in almost every photograph from this time. She was an African American who got by pretty well, all things considered, in an era of Jim Crow laws and bald-faced racism in America. For years she had been solo-tutored in dance, as no ballet school in Seattle would accept her. Generous even as a girl, Fort organized dance classes for the smaller children in her neighborhood to pass on what she learned, an experience which presaged her later fame as a teacher in New York. But where other schools said no to Fort, Cornish said yes. There’s nothing much about her in the school records—though, admittedly, much is lost—but the impression is that she was accepted at Cornish without much fuss of any kind, no complaints on the one hand and no institutional self-congratulation on the other. Fort stayed at Cornish for five years, completing the course; it may be assumed that she was happy at the School, or at least content.

Merce Cunningham and the Actors

Bird’s first order of business on discovering her withered department was to attract more students. Due in large part to the open structure of the school under Nellie Cornish, theater students were required to take dance. Bird managed to entice a few theater majors, such as Jack Tyo and Cole Weston, son of famed photographer Edward Weston, to spend more and more time in dance. She was especially taken with a lanky young man named Mercier Cunningham. Cunningham, “Merce” to his friends, had taken a good deal of dance in his younger years in small-town Centralia, Wash. Cunningham was not thriving in his drama classes, and Bird offered him a chance to express himself in a way that bridged drama and dance. Bird could see something special in him, even then. “Even though he was still raw,” Bird told Bell-Kanner, “he had a magical quality that wowed people.”

It was not long before Cunningham transferred to the Dance Department.

Site-Specific Dance and Social Justice

The summer before she took over the reins at Cornish, Bird met the man she was to marry, Ralph Gundlach. Gundlach was a professor at the University of Washington and deeply interested in political action on the left. Bird was attracted to these causes, too. She felt strongly about the cause célèbre of the moment, the Spanish Civil War, in which General Franco enlisted the aid of Nazi Germany to crush the elected government of the Republic. This interest in social action informed her work at Cornish from very early on. One of the first pieces she and her nascent resident company produced raised money for medical supplies for Spain. The piece presented was Skinny Structures presented sometime, probably, in the fall term of 1937.

There were some fascinating aspects to the dance that show us today the kind of teacher Bird was and what the “Bonnie Bird Company” stood for. First, it was a site-specific piece—at least in its first iteration—choreographed into and through a row of adjoining “skinny houses” built by Gundlach and a group of UW professors on narrow lots. In 1937, modern dance was still very new itself, and the added element of being site-specific was very daring and very imaginitive. Second, putting Bird’s collaborative impulses on display, Skinny

Structures was designed with the ensemble, which included Fort, Cunningham, and Herrmann. The piece was restaged in the Cornish Theatre (now the PONCHO Concert Hall) the next year.

From this small first step, the socially active work of the company grew. At the end of the next term, in May 1938, they were featured in “Dances for Spain,” a much larger effort. The core group was joined onstage by theater students and Cunningham housemates Jack Tyo and Cole Weston.

John Cage

For her first year at Cornish, Ralph Gilbert had accompanied and composed for Bonnie Bird and the Dance Department. As were so many at the school, Gilbert was poached by Martha Graham. He went on to a successful career writing and performing in New York. During the following summer of 1938, while at the Mills/Bennington workshop in Oakland, Bird was on the prowl for someone to replace Gilbert. She was introduced to a young composer who had studied with Schoenberg, John Cage. Cage warned her that he was an experimentalist, and Bonnie, fresh from her experiences with Skinny Structures and Dances for Spain, assured him that she was, too.

Bird and Cage started from the same page, but problems were still there. Nellie laid it all out in a letter to Cage on August 25, 1938 about his incipient hiring. “The Dance Dept. [sic] is small, as we have changed faculty too often recently, and Miss Bird is virtually starting from scratch. ” It got worse. “For this reason, the salary has to be very small.” This did not dissuade him. Cage and his wife, Xenia—who would go on to become a long-time figure in the New York art world—decamped California for Seattle.

Cage had been engaged as an accompanist, but also as a composer for dance, just as Gilbert had been. Soon after arriving at Cornish, he also became a member of the faculty teaching a class in composition.

With the addition of Cage, for the 1938 academic year, the “Bonnie Bird Group” was fully formed. From all indications, Bonnie Bird led her department in a very free and exciting exploration of dance, theater, and music. The photos themselves reveal work that was offbeat and fun. There is one key story, though, that displays how the work unfolded. Arriving at a studio for class one day, Bird and Cage found that no piano had been provided for accompaniment. Rather than cancel, the decision was somehow made for John Cage to lead a wild percussion accompaniment using whatever objects and surfaces were available in the space. This might seem fun and trivial, but it speaks volumes about the relationship of Bird and Cage, and the complete integration of Cage into the fabric of the class. It is also the first glimmerings of a direction for Cage’s music that would make him famous.

It is the year 1938 that Casey Jones came to the stage of the Cornish Theater.

Bird choreographed (and possibly designed the costumes), the dancers danced,

John Cage organized the music, and Xenia Cage designed the set. The whole piece

was set to percussion music, Cage’s most recent obsession. For it, he contacted

a number of avant garde composers he knew. Cage would go on to found one of

the first percussion orchestra ever at Cornish, made up of himself, Xenia,

and some actors, dancers, and music students. The instruments were whatever

was at hand or could be fabricated. The group toured the West Coast. Later,

some music students were added to the group.

It Begins to Unravel

During the summer, Bird took Cunningham and Herrmann to Mills with her to work with Martha Graham. Graham was impressed with her students. As she had done with Bird herself, Graham invited both to join her company. Herrmann had fallen in love with Cole Weston, and so declined. Merce Cunningham, on the other hand, followed Bird’s lead to the letter, accepting the invitation to go to New York a year short of completing his degree. For Bird it was a fiasco; the department was paper thin as it was without losing a dancer of his talent. Her worries extended to Cage and what plans, if any, were in the works for him as the School prepared for life without Nellie Cornish.

“John Cage is giving a concert next Thursday at Mills College,” wrote Bird to the assistant head of school on July 29 of that year. “The people here are very impressed with him—he is restless because of the [writing illegible] to reach a conclusion.”

By the start of 1939, having experimented throughout the prior year and come to terms with the dire departmental situation, Bonnie Bird was ready to formalize a solution for dance at Cornish. Her solution was inventive as it was bold. She proposed starting a professional resident company at Cornish coupled with an aggressive appeal to high-school-age dance students. Bird’s proposal was made in the face of the reality that Nellie Cornish was in her last months as director. Perhaps for this reason, her idea was rejected.

She rescued half of the proposal, and as 1940 began and with it the spring term, Bird gathered young dancers and put them to work on a project that was part Cornish, part independent. It would go on to produce America Was Promises on the Cornish stage, which Bird choreographed, in large part to the spoken poetry of Archibald MacLeish.

The new term also began without Nellie Cornish. The forces that had been pushing for change allied with those seeking to fill the power vacuum left by the director’s departure. Bonnie Bird’s program had, it seems, not been terribly popular in many quarters, and this was about to come home. By February and March, the acting director informed John Cage that his contract would not be renewed and Bird that she would no longer be head of the department., in spite of the fact she was also the head of faculty at Cornish. Cage’s firing and Bird’s demotion were part of a general restructuring of Nellie’s faculty and curriculum.

Offered the opportunity to teach separate classes at Cornish for whatever she could make on percentage, Bird declined. On contract through May of 1940, she planned to take the beginnings she had made towards a resident company at Cornish and make it an independent school.

As the academic year ended, so had an era. Bird had her new school in the U District, Merce was in New York, Cage and Xenia were in Chicago working with the New Bauhaus, and Dorothy Herrmann, Cole Weston, and Syvilla Fort graduated, soon to relocate to Los Angeles. And Nellie Cornish herself had left the scene.

Other than a sketchy trail of documents and what we can make of them, Phyllis Dearborn’s pictures of the Bonnie Bird Company are what we have of this signal moment for Cornish and, indeed, for arts education in the last century.